Prohibition came to Wilmington and the country on January 17, 1920, one year after the ratification of the 18th Amendment to the Constitution. The National Prohibition Act, informally known as the Volstead Act, prohibited the production, sale and transport of intoxicating liquors. Almost immediately, the underworld of the illegal liquor trade spread its roots and became entrenched in every city and town across the nation. For Wilmington’s part, illegal booze production soon sprang up in the four corners of the town and nearly everywhere in between. The benefit of beginning such an enterprise was not lost on many of the townspeople. Money would, no pun intended, pour into the pockets and purses of those so inclined to enter such a trade. Conversely, the pitfalls were minimal to non-existent. The choice for many was a foregone conclusion.

In 1920, the town’s paltry police force consisted of only one full time officer, Chief Walter Hill. Under his wing, a contingent of would-be enforcers numbered only a dozen or so special officers. The specials were appointed to work as police officers but only as needed or as it was affordable to the town. Hill and his force however, at the dawn of the dry age, initially had the assistance of the local State Police Patrol and a resident federal Prohibition Agent. Still so, the chief and his officers were often reluctant to be heavy-handed with friends and neighbors. Furthermore, the good chief was known to imbibe from time to time, sometimes more often than not. On the other hand, the federal Prohibition Bureau’s top enforcement agent in the state, Harold D. Wilson lived on Church Street. A strict Prohibitionist, he employed his own agents, but often called upon the State Police Patrol and Wilmington’s chief and special officers for local raids. Hill and his officers where often unenthusiastic with Wilson’s overzealous methods, especially with people they knew. In one instance, a special officer assigned by Wilson to guard the rear of a house being raided reported to the agent that he did not see anything of consequence except a woman dumping buckets of “water” out a back window. Wilson was far from pleased with the police department’s lackluster attention to what he considered his own personal mandate. However, Wilson soon ran afoul of his own superiors, the state’s political bosses and their patrons. In December of 1921 he led a raid on the Quincy House in Boston. Liquor abounded but so did a host of powerful politicians as the Scollay Square hotel was serving as a venue for a party honoring Governor Channing Cox. Wilson was sacked by his Washington bosses two months later. The State Police Patrol similarly left town as well. The quarters that they had set up at the West School in 1922 were vacated in 1924 for a larger station in the neighboring town of Reading. By 1925, it was just Chief Hill and a few special officers left to police the town’s rum trade. All the better presumably thought many a resident, including the Widow Rebecca Goldberg.

Rebecca Goldberg (nee Wernick) was a Jewish immigrant from Vilna, Lithuania who in 1889, escaped the oppression of Tsarist Russia and came to the United States. After marrying in 1900 she eventually settled in Wilmington on the whim of her husband’s chance meeting with a convincing land speculator. Despite Rebecca’s initial protestations, the parcel of land, “off of Thurston Avenue,” as town property valuation records indicate, was purchased. Despite some initial setbacks the land soon provided the family with a home and a small poultry house. Sadly though, Rebecca was widowed in 1918 when her husband was involved in a trainyard accident. Nathan Goldberg was caught beneath a switcher engine at the South Wilmington railyard in Woburn. On his way to work at a North Woburn factory, he had just alighted a B&M passenger train when he was struck. The accident severed both his legs below the knees, fatally injuring him. In the aftermath of that tragedy, Rebecca found herself in a precarious position. She had a small egg selling business in Boston to which she traveled from Wilmington by train but was it sufficient for the expenses of the family absent the income of her husband? That question was soon answered in 1920 when Prohibition became the law of the land and Rebecca was swayed to enter into the illicit liquor trade. A connection in Chelsea would supply Rebecca with raw alcohol which she would bring back to her home and turn into blueberry wine. The purple fruit grew in abundance nearby and perfectly combined with the clear spirits to make a palatable and profitable drink. One of Rebecca’s many customers was none other than Chief of Police Walter Hill.

To say the liquor business thrived in Wilmington would be an understatement. For every still that was smashed and every barrel that was broken many more sprang forth to take their place. Rebecca’s venture, however, was far more subdued. She did not distill the spirits herself. She did not smuggle copious quantities. She did not have a manufacturing facility. Instead, she carried jugs of alcohol home in her empty egg suitcases. Her daughter secretly made deliveries to residents and local officials and her son collected discarded bottles from the roadside and town dump. All of her children took part in picking the blueberries. Occasionally, trusted residents picked up their pints from her at her home. However, the rampant liquor manufacture and trade (of which Rebecca was ultimately a part) soon caught the ire of the selectmen. Dissatisfied with Chief Hill’s efforts, the three-man board soon took matters into their own hands. Without informing the chief, they hired two private detectives and appointed them special police officers. They then sent them out about the town and had them mingle and gain the trust of the residents, especially those suspected of being rum runners. One such visit they made was to Rebecca Goldberg’s home, colloquially known as the Tavern in the Woods.

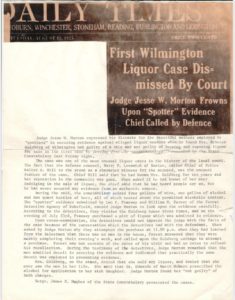

In 1925 Rebecca Goldberg was caught in a sting perpetrated by the private detectives surreptitiously hired by the selectmen. One August evening that year, a knock came on Rebecca’s door at near midnight and upon opening it she was faced with two unknown men wanting to make a purchase. Suspicious, she deposited a pint on the step and closed the door. The next morning seventy-five cents sat in place of the bottle. Within a few days however, Wilmington Police raided the Goldberg home and confiscated the liquor found therein. Although, they “missed” the main stashes of booze secreted in the dining room table and the chicken coop. Summoned to appear before Judge Jesse Morton at the district court in Woburn, Rebecca entered a plea of not guilty. Soon after, Judge Morton began examining and questioning the unscrupulous tactics employed by the selectmen’s “spotters” as they were referred to in the press. How dare they visit the home of a widow so late in the evening knowing there were no men present Judge Morton exclaimed, seemingly damaging any testimony that might be offered by the private detectives. Rebecca’s lawyer then further damaged the Commonwealth’s case when he called Chief Hill to the stand as a character witness for his client. Chief Hill testified that he had known Mrs. Goldberg for ten years and that she was a good and reputable woman within the community. He was also questioned as to whether he knew if she was part of the illicit liquor trade. The answer the chief offered soon sealed her fate. He reported to the judge that while he had heard rumors, he had never secured any authentic evidence against her. Judge Morton summarily declared Rebecca Goldberg “not guilty,” being dismayed by the tactics of the selectmen’s spurious private police force.

In the end, the town coffers were $600.00 lighter that year, the money to pay for the spotters and their eventual legal debacle ironically coming from the police department’s own budget. Chief Walter Hill remained in office and continued to serve until his passing in 1932. The 18th Amendment was eventually repealed on December 5, 1933, and in 1940, Rebecca Goldberg passed away.

Special thanks to Marian Leah Knapp, Rebecca Goldberg’s granddaughter and author of Prohibition Wine A True Story of One Woman’s Daring in Twentieth-Century America.

RETURN TO 150 YEARS OF STORIES