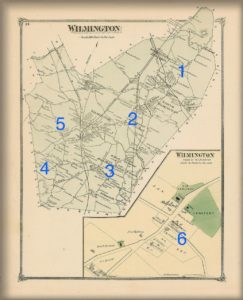

In case of emergency call 9-1-1. That statement seems simple enough in today’s technology driven society, the touch of three buttons and help is on the way. A voice command reduces that task to even simpler terms. From Wilmington’s cellular towers, church steeples and water standpipes, each bristling with antennae, emanate the signals that summon the requested help. Computer aided dispatch and mapping applications pinpoint locations. Radio transmissions and web interfaces direct and relay vital information. The police cruisers arrive speedily with officers ready to act. But what about a century and a half ago? The accompanying map of the town from that era will help tell the story.

In case of emergency call 9-1-1. That statement seems simple enough in today’s technology driven society, the touch of three buttons and help is on the way. A voice command reduces that task to even simpler terms. From Wilmington’s cellular towers, church steeples and water standpipes, each bristling with antennae, emanate the signals that summon the requested help. Computer aided dispatch and mapping applications pinpoint locations. Radio transmissions and web interfaces direct and relay vital information. The police cruisers arrive speedily with officers ready to act. But what about a century and a half ago? The accompanying map of the town from that era will help tell the story.

Wilmington’s first police officer, A. Porter Pearson (1), lived on Andover Street more than two miles from the North Wilmington train depot and half that distance again from the town hall. The depot at Wilmington Center was a full four miles from his home. The town hall was at the geographic center of the town and the area also served as its religious center as well. Both train depot locales were fairly well settled as business and residential enclaves. Yet, even by horse drawn carriage, a trip from any of these places to summon him at his home and his return trip in response could take an hour or more. His timely response to any of the outlying regions of town would only be further hindered by the increased distances. The grand experiment to introduce the services of a police officer might otherwise fail if its reliance rested solely on the shoulders of single man living far removed from the populace.

In 1873 the Board of Selectmen sought to change these circumstances by appointing four additional townsmen to the position of special police officer. In doing so they dotted the landscape of the town with able men, slashing the distances residents and officers would need to travel.

While their residences about the town undoubtedly played a role, the newly appointed men were also somewhat prominent in their own right. Zebard T. White (2) was originally from Winchester but after marrying Lydia Shedd of Woburn in 1867 they moved to Middlesex Avenue near present day Mystic Avenue. Z.T. White, as his house is noted on the 1875 map, was a tanner and currier (two trades of the leather industry). His home’s proximity and his occupation suggest that he was employed at the Perry, Cutler & Company Tannery (later the C.S. Harriman Tannery). Charles W. Swain (3) was similarly self-employed like A. Porter Pearson as both a farmer and a shoemaker, making his home on east side of town at the intersection of Lowell and Woburn Street. He descended from the Gowing Family on his mother’s side and two years before his appointment as a special police officer, he founded the Wilmington Library. Noah Clapp (4) operated a sawmill in the ancient section of town known as Wood Hill. It is said from his sawmill came the timbers of the Congregational Church, built after the Bond Bakery conflagration of 1864 had destroyed the town’s second meetinghouse. Stephen Otis Butters (5) lived at or near the William Boutwell House on present day Boutwell Street. He is not indicated by name on the 1875 map, but federal census records suggest he was living at the Boutwell House with his occupation being that of a farmer. He was a direct descendent of William Butter who settled on present day Mill Road (then part of Woburn) in 1665. Samuel B. Nichols (6) was the town’s elected constable. He had previously been the town’s liquor agent, dispensing medicinal remedies in the regulated and otherwise dry town. His primary occupations while constable was that of storekeeper and undertaker. His former home at the intersection of Middlesex Avenue and Wildwood Street still stands and remains in name, the funeral business he founded.

Despite these appointments however, communication and travel remained slow. These men, while willing, were also otherwise employed. A resident seeking Zebard White for assistance might more readily find him working hides at the tannery. One might have to shout above the din of the mill’s waterwheel and sawblade to summon Noah Clapp and the other special officers might very well have to be found while at work in their fields or workshops. The special officers might not always have the convenience of a horse or carriage either. In responding to minor nuisances and petty crimes, walking was almost certainly preferred method of response. Horses were a valuable asset, especially to the hardscrabble farmer. Yet, as imperfect as it might have initially been, this new venture to make police officers readily available to serve became and remained a success. Foot travel and horse drawn carriages gave way to bicycles and streetcars and automobiles. A knock on the door of a shoemaker’s house or a farmer’s barn gave way to a telephone call being answered at a police station. Easily demonstrated today, the legacy of these early officers remains alive whenever a person in need calls 9-1-1.

RETURN TO 150 YEARS OF STORIES